Three tests to confirm the diagnosis of acquired hemophilia – infographic

Acquired hemophilia (AHA) typically manifests with spontaneous bleeding in patients with no prior personal history of significant bleeding.1–4 The cause of the bleeding is a significant decrease in FVIII activity induced by autoantibodies against coagulation factor VIII.5 In polymorbid patients, established antithrombotic therapy at the time of AHA diagnosis may also contribute to the bleeding.4

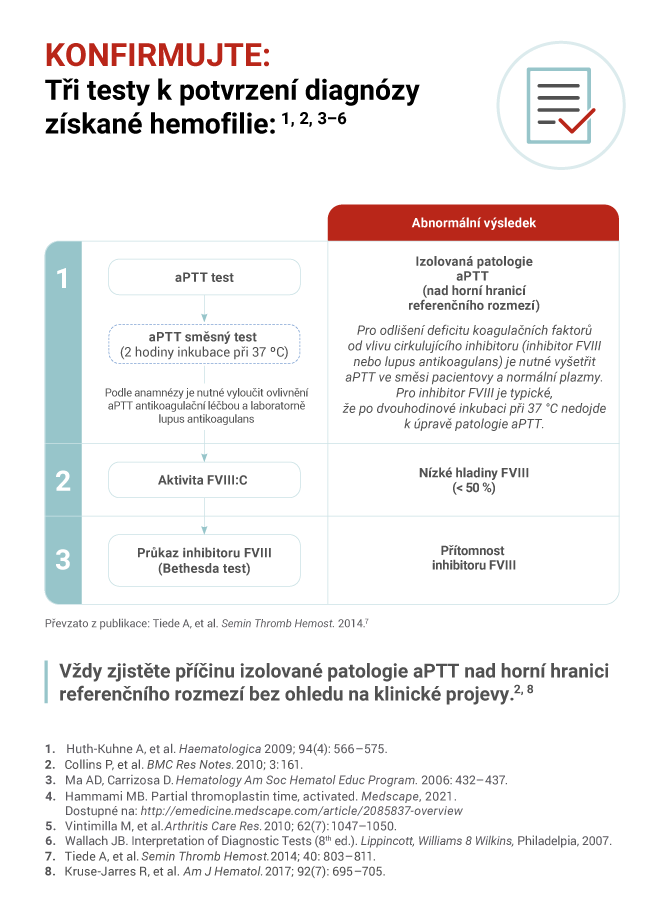

In basic laboratory test results, the reduction in FVIII activity is reflected by an isolated prolongation of activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT). Prothrombin time, fibrinogen concentration, and platelet count are within the reference range. Unexplained bleeding plus isolated prolongation of APTT is a signal for immediate confirmatory testing.4, 5 A simple diagram is provided in the image.6–11

For the differential diagnosis of isolated APTT prolongation, it is necessary to exclude the influence of anticoagulants (pharmacological history), perform mixing studies with APTT evaluation immediately after mixing the patient's plasma with control plasma, and APTT after 2 hours of incubation of the mixture at 37°C. Based on the results of the mixing studies, conduct tests confirming/excluding FVIII inhibitor (determine its titer), lupus anticoagulant, another nonspecific inhibitor or deficiency of another coagulation factor – FXII, FXI, FIX, FVIII, and vWF:Ag.4, 11

The diagnosis of AHA is given by the evidence of reduced FVIII activity combined with the evidence of a specific FVIII inhibitor (today most commonly via the Nijmegen modification of the classical Bethesda assay12). Very low FVIII activity (<1%) is associated with a lower probability and longer time to remission, or with higher overall mortality13–15. Similarly, a high inhibitor titer may indicate a lower likelihood of achieving remission or a slower response onset.14, 15

Literature:

1. Knoebl P, Marco P, Baudo F et al. Demographic and clinical data in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). J Thromb Haemost 2012; 10 (4): 622–631, doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04654.x.

2. Borg JY, Guillet B, Le Cam-Duchez V et al. Outcome of acquired haemophilia in France: the prospective SACHA (Surveillance des Auto antiCorps au cours de l'Hemophilie Acquise) registry. Haemophilia 2013; 19 (4): 564–570, doi: 10.1111/hae.12138.

3. Collins PW, Chalmers E, Hart D et al. Diagnosis and management of acquired coagulation inhibitors: a guideline from UKHCDO. Br J Haematol 2013; 162 (6): 758–773, doi: 10.1111/bjh.12463.

4. Tiede A, Collins P, Knoebl P et al. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica 2020; 105(7): 1791–1801, doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.230771.

5. Knoebl P. Prevention and management of bleeding episodes in patients with acquired hemophilia A. Drugs 2018; 78 (18): 1861–1872, doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-1027-y.

6. Huth-Kuhne A, Baudo F, Collins P et al. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of patients with acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica 2009; 94 (4): 566–575, doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.001743.

7. Collins P, Baudo F, Huth-Kuhne A et al. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. BMC Res Notes 2010; 3 : 161, doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-161.

8. Ma AD, Carrizosa D. Acquired factor VIII inhibitors: pathophysiology and treatment. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2006 : 432–437, doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2006.1.432.

9. Vintimilla M, Joseph A, Ranganathan P. Acquired factor VIII inhibitor in Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010; 62 (7): 1047–1050, doi: 10.1002/acr.20147.

10. Tiede A, Werwitzke S, Scharf RE. Laboratory diagnosis of acquired hemophilia A: limitations, consequences, and challenges. Seminars Thromb Hemost 2014; 40 (7): 803–811, doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390004.

11. Kruse-Jarres R, Kempton CL, Baudo F et al. Acquired hemophilia A: updated review of evidence and treatment guidance. Am J Hematol 2017; 92 (7): 695–705, doi: 10.1002/ajh.24777.

12. Verbruggen B, Novakova I, Wessels H et al. The Nijmegen modification of the Bethesda assay for factor VIII:C inhibitors: improved specificity and reliability. Thromb Haemost 1995; 73(2): 247–251.

13. Tiede A, Hofbauer CJ, Werwitzke S et al. Anti-factor VIII IgA as a potential marker of poor prognosis in acquired hemophilia A: results from the GTH-AH 01/2010 study. Blood 2016; 127 (19): 2289–2297, doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-672774.

14. Tiede A, Klamroth R, Scharf RE et al. Prognostic factors for remission of and survival in acquired hemophilia A (AHA): results from the GTH-AH 01/2010 study. Blood 2015; 125(7): 1091–1097, doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-587089.

15. Werwitzke S, Geisen U, Nowak-Gottl U et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of factor VIII binding antibodies in acquired hemophilia A: data from the GTH-AH 01/2010 study. J Thromb Haemost 2016; 14 (5): 940–947, doi: 10.1111/jth.13304.

Did you like this article? Would you like to comment on it? Write to us. We are interested in your opinion. We will not publish it, but we will gladly answer you.